This blog dives into what “Policy is rejected by licensing” actually means inside Windows, why that decision is not based on what Intune reports or what the Microsoft docs promise, and which licensing engine ultimately decides whether a policy is allowed or silently blocked.

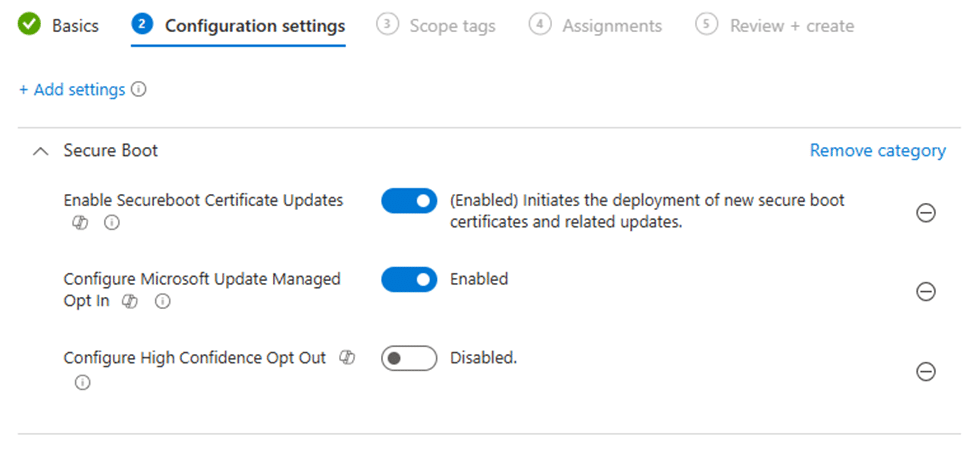

Enable Secure Boot Certificate Updates

The clock is ticking on Secure Boot certificate expiration. Microsoft has documented the steps to rotate those certificates, and Intune provides a built-in policy to do exactly that.

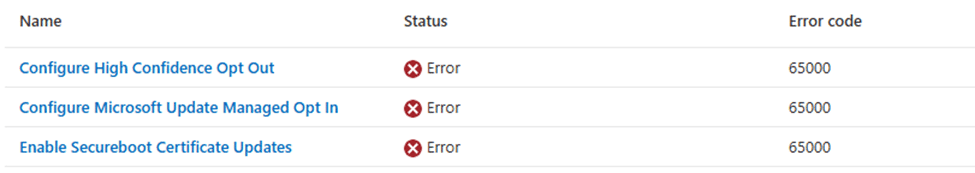

On paper, it is straightforward. You configure the policy, assign it, and Windows takes care of the rest. In reality, many administrators ran into something else entirely. The policy deploys, reporting shows errors, and devices respond with the same familiar status: Error 65000.

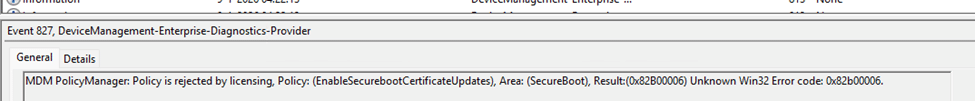

Policy is rejected by licensing and error 65000

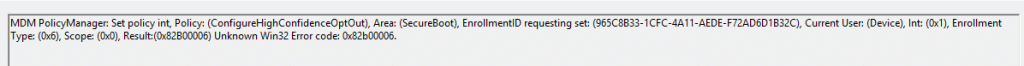

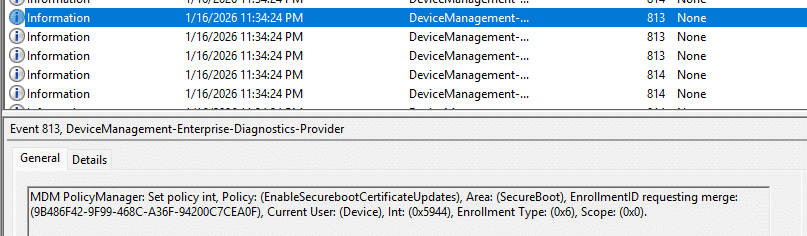

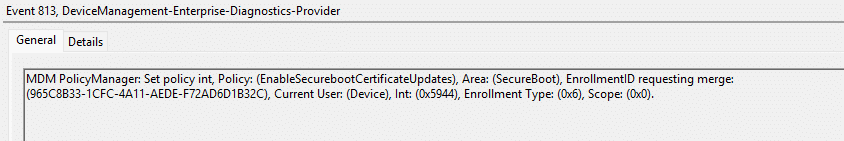

With the 65000 error appearing in Intune, the next place to start is the problem device itself. To be precise, in the Enterprise Device Management event log. In that event log, you will spot an MDM PolicyManager event that is very explicit about the real reason: Policy is rejected by licensing for EnableSecurebootCertificateUpdates, with 0x82B00006.

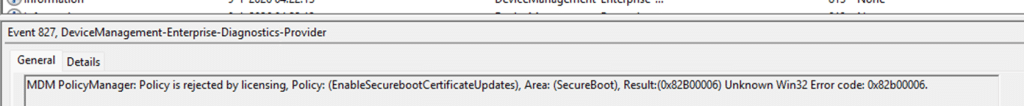

That 0x82B00006 error message is not something new. It has existed for years and typically appears when an Enterprise-only setting is applied to a Pro device. In those cases, the behavior makes sense. (requireprivatestoryonly, doesn’t work on Pro)

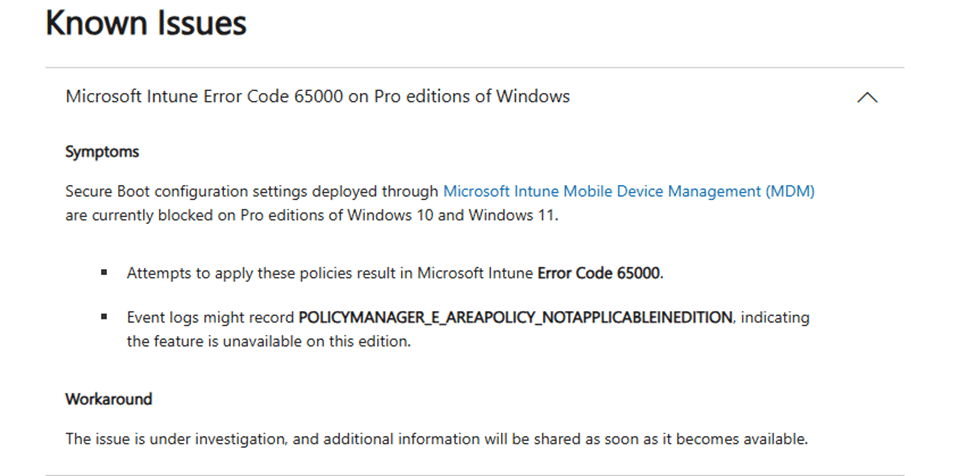

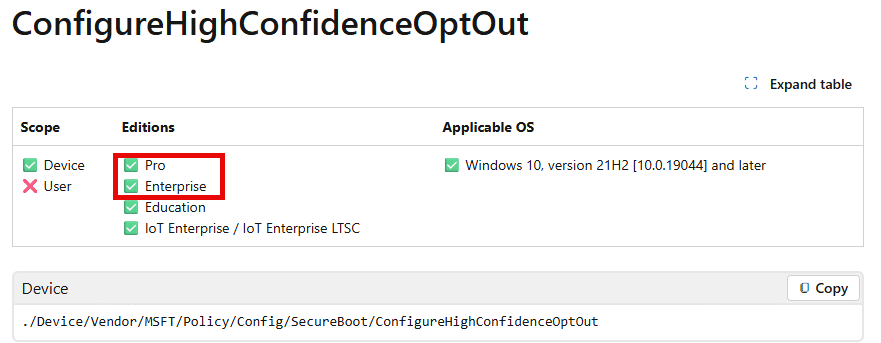

The Secure Boot certificate update Settings Catalog policy, however, is documented as supported beyond the Enterprise scope. That is where the confusion starts. The policy should apply. The device says it cannot and licensing is blamed… which is why it is added as a known issue to the documentation (but isn’t 100% true…. more on that later on)

This is where most investigations end. The Secure Boot policy fails, the error code 65000 is generic, and it has been documented as a known issue. With it, people revert to proactive remediations to set the same policy.

But still…I was curious which decision- making engine is responsible for this error: Policy is rejected by licensing.

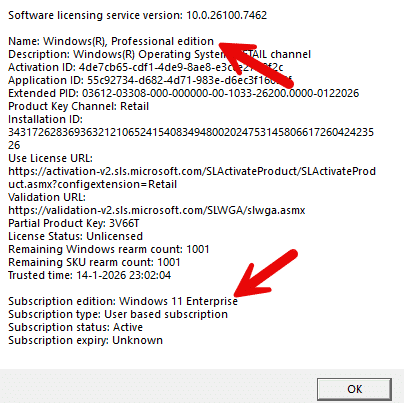

Subscription activation does not change the licensing decision

An important detail often overlooked is that this behavior is not limited to devices running Windows Pro natively. Devices upgraded from Pro to Enterprise via subscription activation are also affected in exactly the same way.

In Intune, these devices are shown as Enterprise, and the activation status on the device also confirms Enterprise. From an administrative perspective, that combination strongly suggests that Enterprise-scoped policies should apply without issue. The licensing engine, however, does not base its decision on how the device is presented in Intune or on the visible activation state. The evaluated MDM policy allows the list to be resolved independently using SKU-specific and internally computed licensing data.

This is why the behavior feels inconsistent. Two devices can both appear as Enterprise, be activated, yet still produce different outcomes. Subscription activation alone does not guarantee that an Enterprise-gated MDM policy is considered allowed by the licensing engine. These policies only apply when you have installed the device with Windows Enterprise from the start!

Once that distinction is clear, the rest of the behavior falls into place.

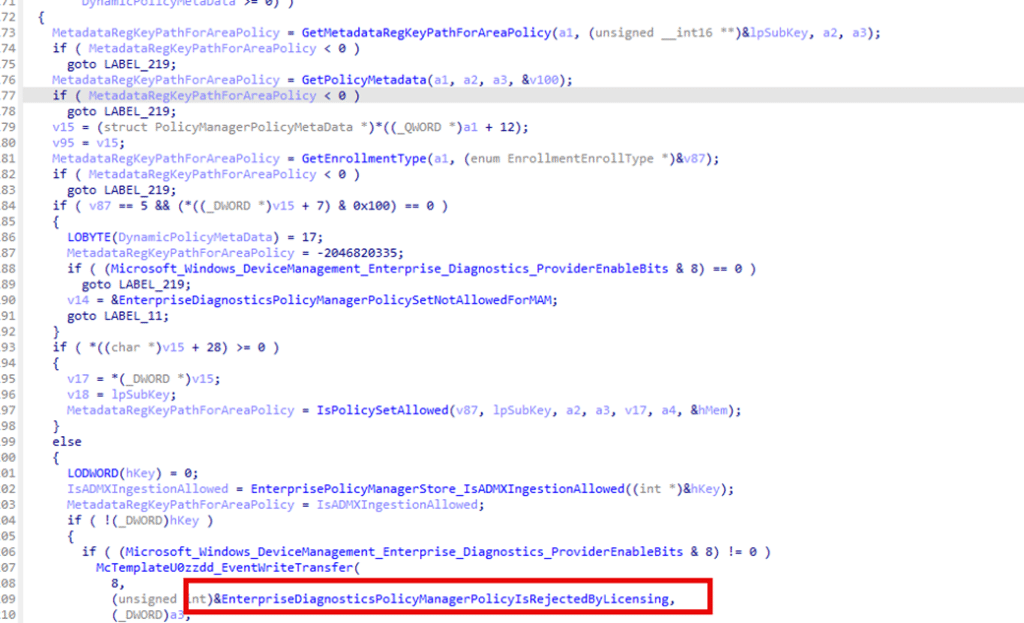

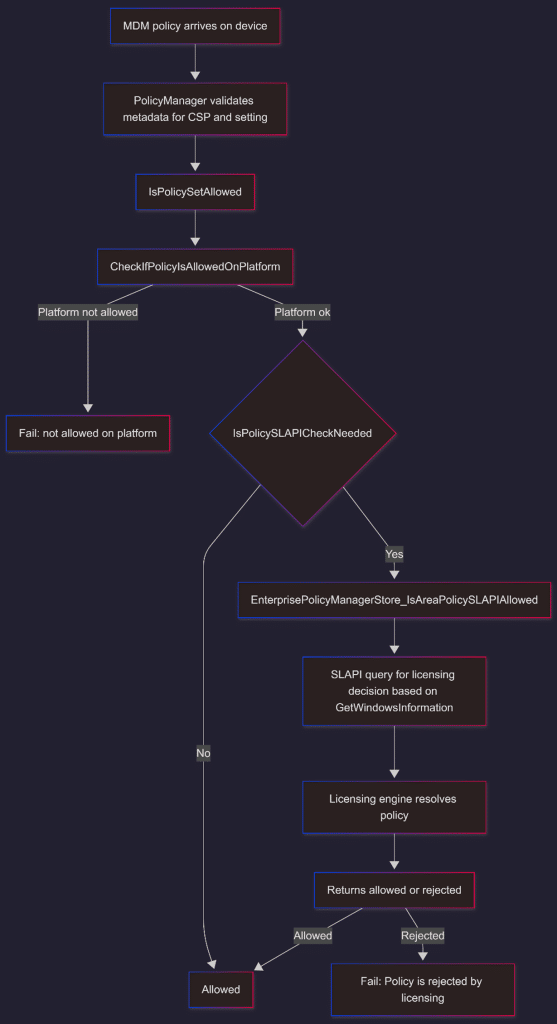

What Actually Happens When a Policy Reaches Windows

When Intune delivers a configuration policy, the Windows MDM stack does not immediately write values to the registry. Every policy flows through the PolicyManager first. One of PolicyManager’s responsibilities is to verify whether a policy is permitted on the device before any action is applied. That validation happens in layers. The policy area is checked. The policy name and enrollment type are checked; from there on, the platform restrictions are evaluated. Only after that does licensing come into play.

This is where many assumptions break down. Licensing is not just about activation state or installed edition. It is a full policy engine with its own rules, inputs, and protected data stores. If licensing rejects a policy, PolicyManager stops processing the policy and shows in the event log that the policy was rejected by licensing.

That means the failure occurs before any setting is applied, even if the policy should apply to Pro and Enterprise devices.

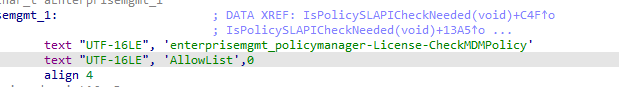

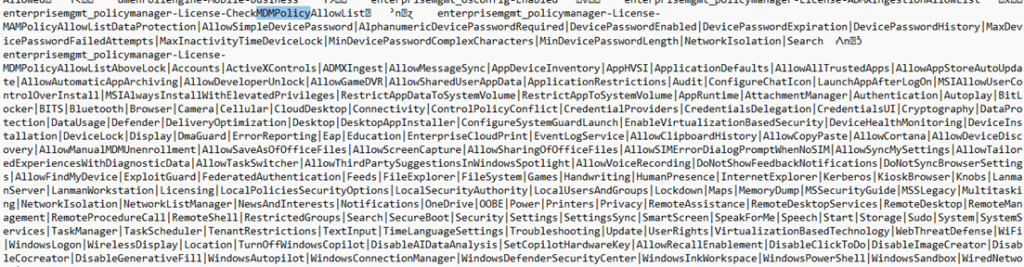

The First Policy is rejected by licensing Clue: MDMPolicyAllowList

While navigating from one function in the policy manager to the next, one name keeps appearing: MDMPolicyAllowList.

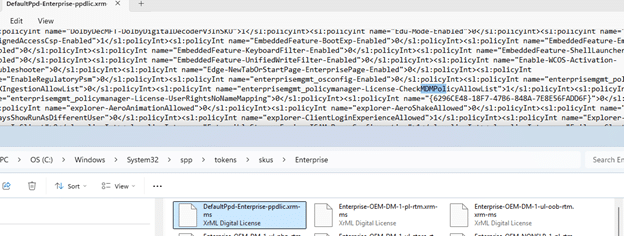

This string appears in multiple places. It appears in all corresponding Windows license files. The Enterprise xrml file, as well as the professional license files.

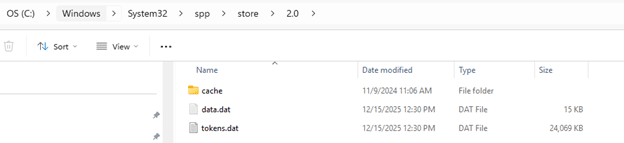

Besides the MDMPolicyAllowList being mentioned in the license files, that MDMPolicyAllowList is also listed in the tokens.dat under the Software Protection Platform (SPP) folder.

At first glance, everything looks correct. Secure Boot-related policies appear inside those MDM allow lists, even on Pro devices. That would suggest the policy should be allowed, right? But the Windows Pro device still rejects it (well, the policymanager). That contradiction is the first real signal that those files are not the final source of truth.

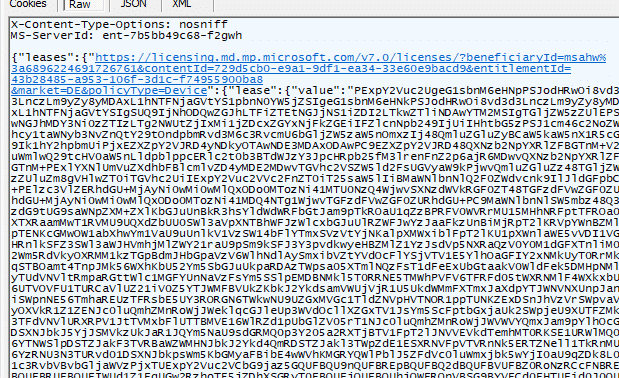

Policy is rejected by licensing: Tokens and License Files

Tokens.dat and the license files in the SPP folder can be considered the decision source. They contain exactly the licensing data that the policymanager was looking for in the SLAPI code MDMPolicyAllowList.

As shown above, the decoded licensing tokens.dat file indeed showed the whole MDMPolicyAllowlist. When Secure Boot appears there (as it clearly did), it is reasonable to conclude that licensing should permit the specific policy. But those files are inputs, not decisions.

They describe potential capabilities…potential… They do not represent an evaluated policy state. Windows never directly uses those files when determining whether a policy is allowed to be applied. The actual decision is made elsewhere.

ProductPolicy: Names Without Answers

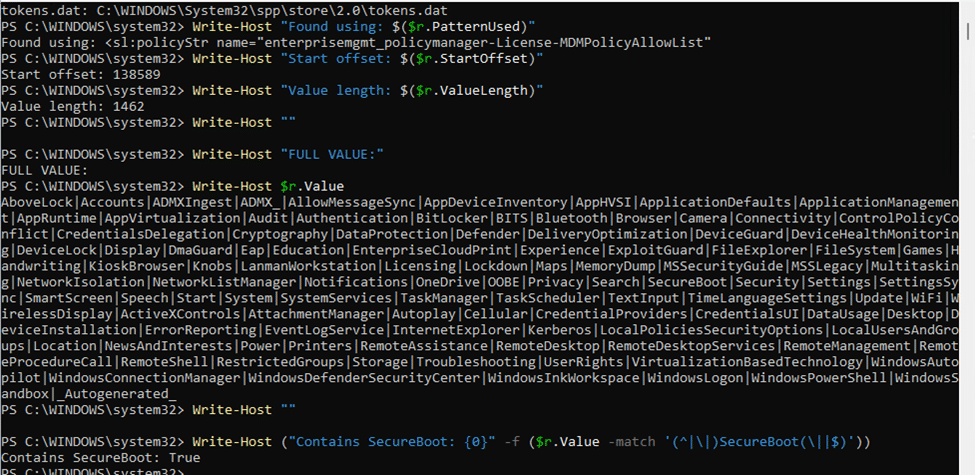

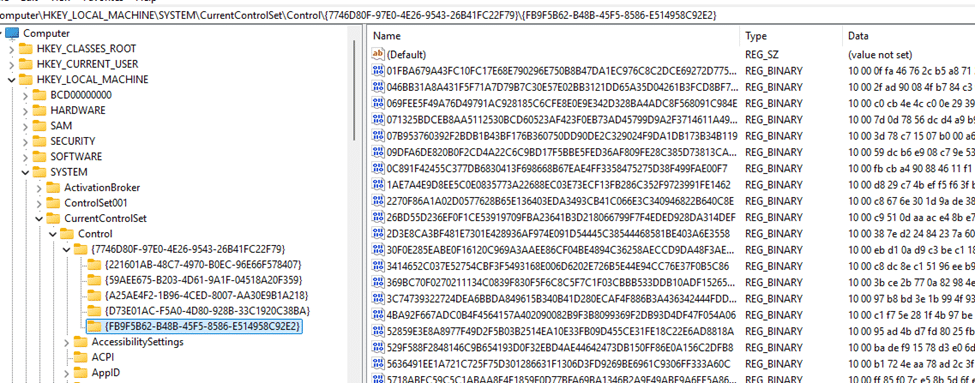

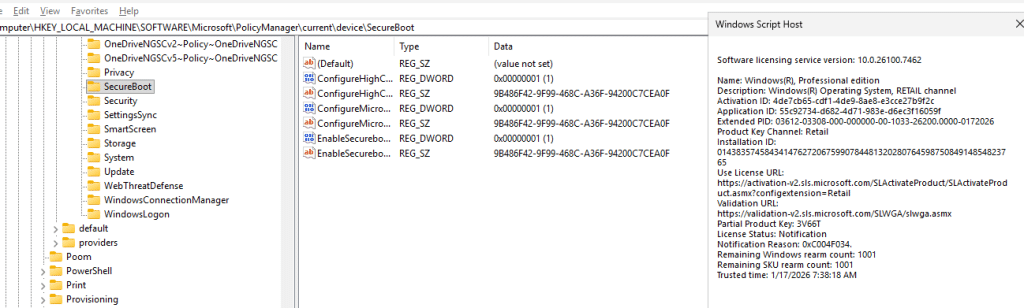

While running a procmon trace and syncing the device, another registry value magically appeared: HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\ProductOptions\ProductPolicy

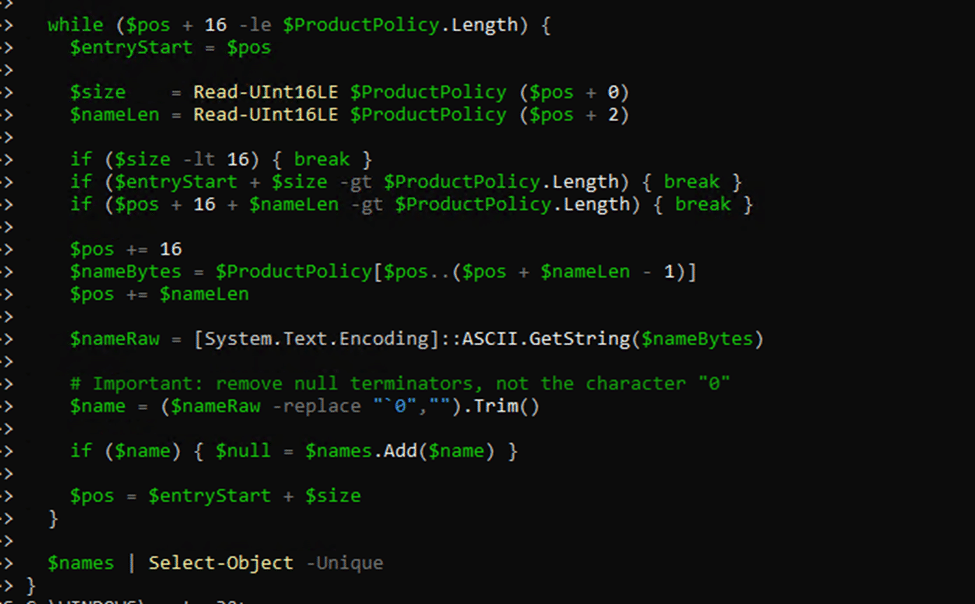

This Productpolicy value is a large hex binary blob. It is unreadable at first glance, but with a few PowerShell commands, the hex value became more readable.

As shown above, the productpolicy registry key indeed again showed the same MDMPolicyallowlist as the tokens.dat. But the ProductPolicy registry key does not store the policy values. It stores policy identifiers. Think of it as an index. It tells Windows which policy names exist, and which ones should be queried. Nothing more…Nothing less.

The ProductPolicy registry key does not tell the policymanager whether Secure Boot is allowed or rejected by licensing. It only says Secure Boot-related policies exist. So Windows uses ProductPolicy to know what questions to ask. Not how to answer them.

Where the Real Answer Comes From

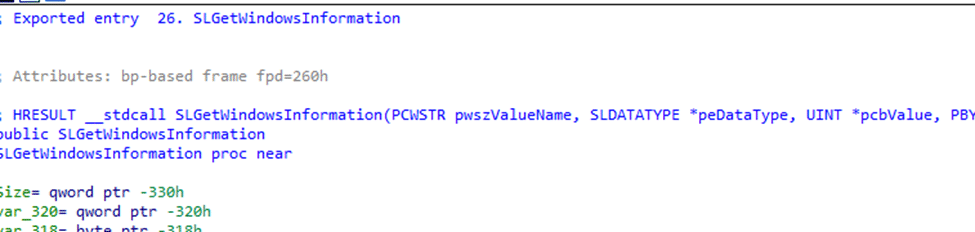

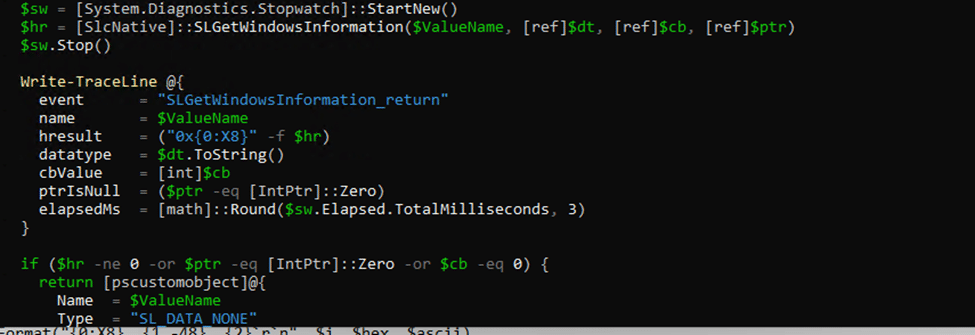

Once a policy name is identified, Windows calls into the Software Licensing API. Specifically, SLGetWindowsInformation.

This is a critical point. The PolicyManager does not parse tokens.dat. It does not decode the ProductPolicy, and it does not directly read the license XML files. The PolicyManager asks the licensing engine a direct question. Is this policy allowed? (MDMPolicyAllowed). If the policy is not allowed, you can guess the outcome: Policy is rejected by licensing

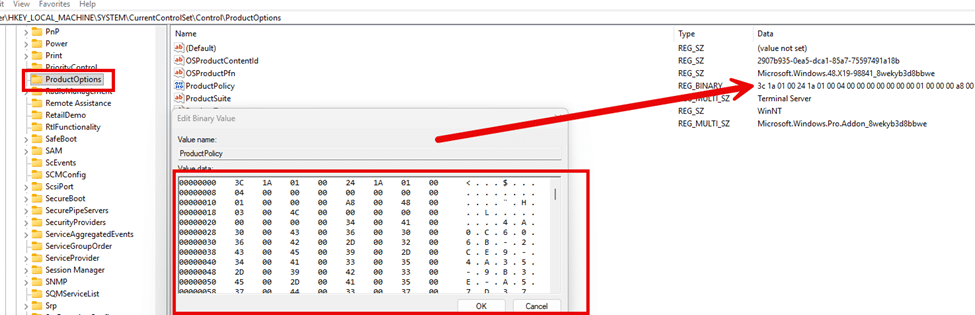

SLGetWindowsInformation is not a simple registry lookup. The call transitions from user mode to kernel mode. From there, it enters the Client License Platform driver. That driver accesses a protected licensing store under: HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\{7746D80F-97E0-4E26-9543-26B41FC22F79}

This is not a normal registry key. It is a compiled, protected licensing database (you need psexec to access it). It contains evaluated rules. SKU-specific gating. Feature restrictions. Edition boundaries. This is where Pro versus Enterprise actually matters.

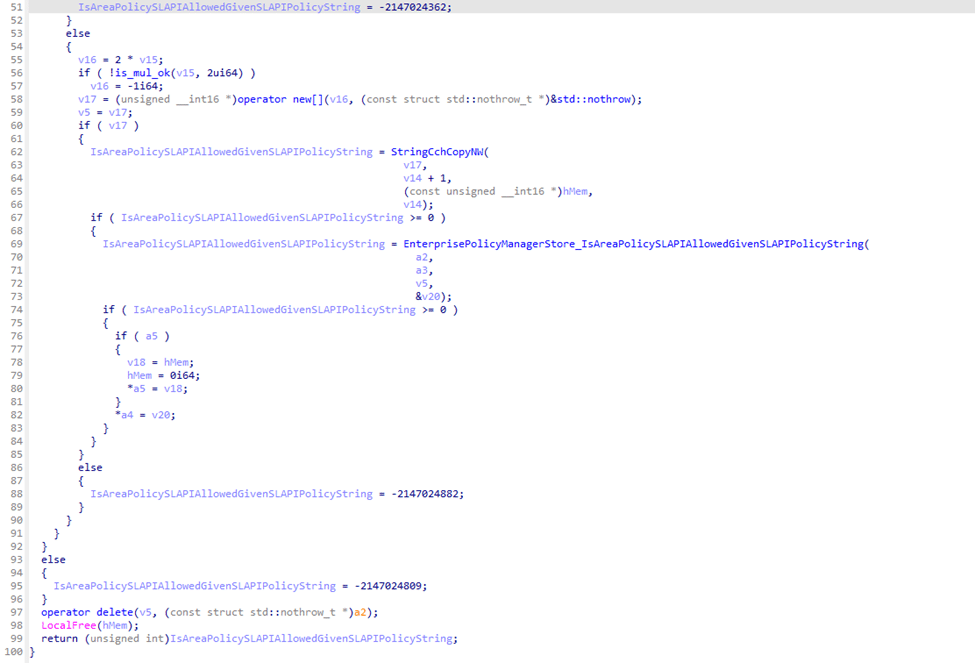

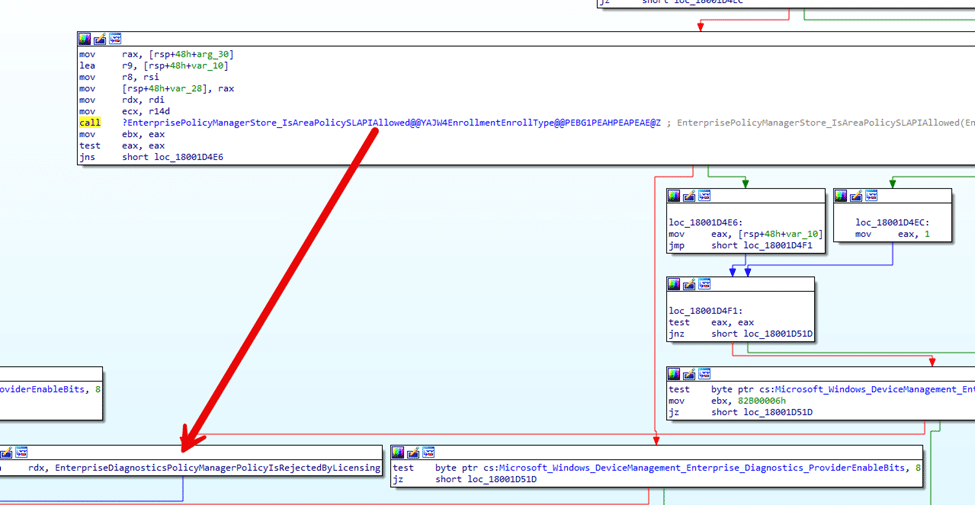

The PolicyManager Licensing Check in Plain Terms

Within the PolicyManager (DLL), every policy follows the same logic. Once platform checks pass, PolicyManager asks whether a licensing check is required. For many security-related policies, the answer is yes. When that happens, the PolicyManager calls into the SLAPI path and requests a string-based policy value.

That string includes the policy namespace, the area, and the enrollment context.

The licensing engine responds with a single authoritative answer. Allowed or not allowed. If the answer is not allowed, PolicyManager emits an event stating the policy was rejected by licensing and returns error 65000 to the MDM stack.

Why Secure Boot Disappears on Pro

Once the investigation reached this point, the behavior finally made sense. On Enterprise devices, Secure Boot appears in the evaluated licensing data. On Pro devices, it does not. Even though Secure Boot exists in license files and tokens, the licensing engine resolves the final allow list differently depending on the SKU and build state.

When PolicyManager asks SLAPI whether Secure Boot is allowed, the answer returned on Pro devices is simply no. PolicyManager does not question that answer. It reports the policy as rejected by licensing and exits.

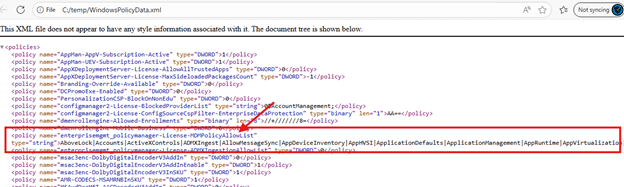

Why LicensingDiag Shows the Truth

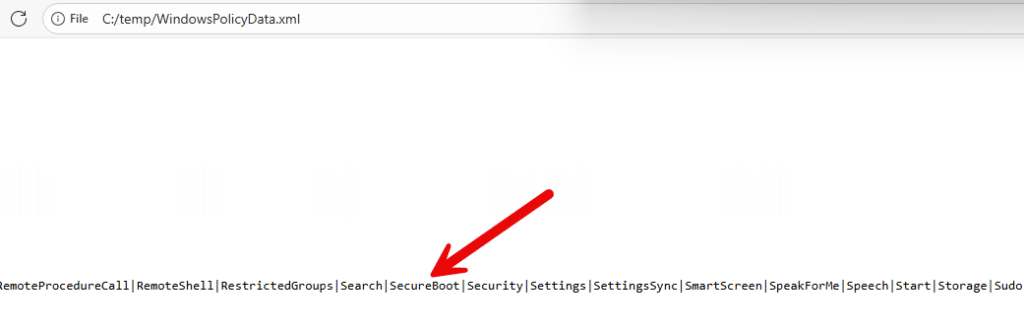

This is where the LicensingDiag tool comes into play. The LicensingDiag tool does the same thing as the policymanager. It calls the same licensing APIs used by PolicyManager and exports the evaluated results into WindowsPolicyData.xml.

That XML file reflects precisely what licensing believes is allowed on the device at that moment. When Secure Boot does not appear in that XML on Pro devices, it explains everything. The policy is rejected because some internal licensing says no.

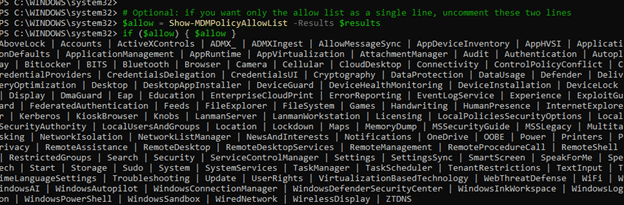

PowerShell script to check: Policy is rejected by licensing

To confirm this behavior, we wrote a PowerShell script that mimics the same MDM Policy flow.

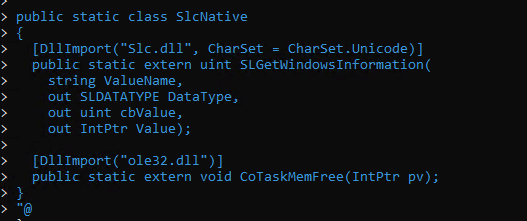

The script first imports the slc.dll… as that’s the DLL the GetWindowsInformation function lives in.

From there on, it reads the ProductPolicy catalog from the ProductOptions registry key and extracts each policy identifier.

For each extracted identifier, it calls the SLC.DLL function: SLGetWindowsInformation.

The result matches LicensingDiag exactly. Secure Boot is only allowed on Enterprise (Again, not Pro upgraded to Enterprise). It is missing on Pro. Different tools. Same licensing engine. Same answer.

Subscription Activation Is the Problem

That made me wonder… what if this whole “policy is rejected by licensing” problem is simply SLAPI not recognizing subscription activation for this Secure Boot policy? A regular Enterprise device applies the policy without issues. But a Pro device that only became “Enterprise” through subscription activation still gets blocked.

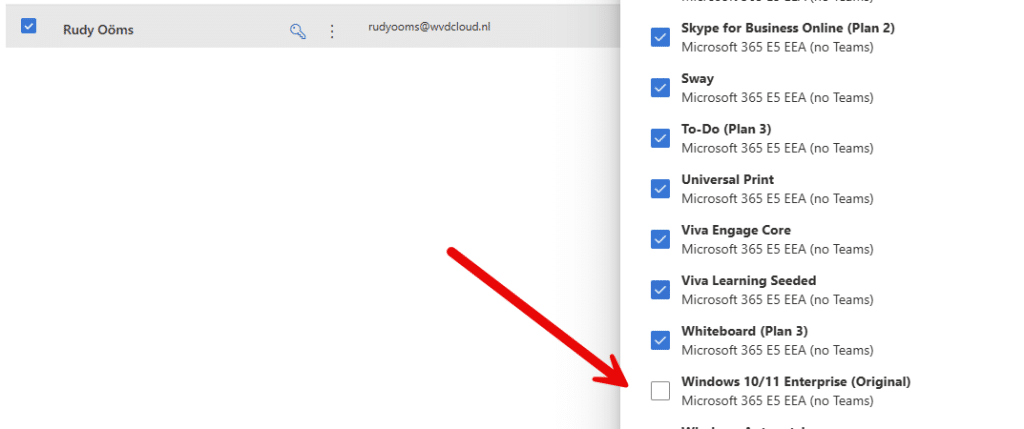

So to test that theory, I removed the Windows Enterprise license from my E5 stack for my user.

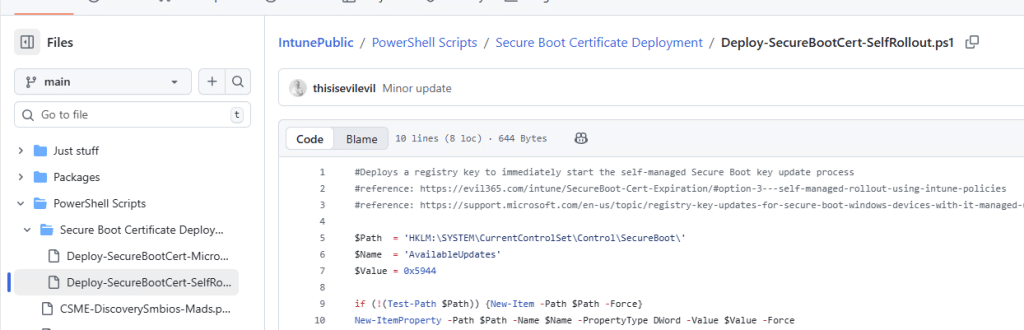

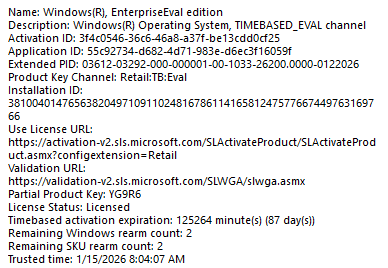

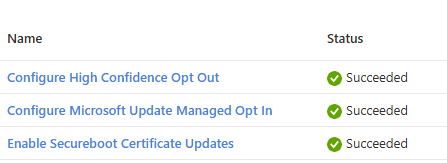

I reinstalled the same device with Windows Pro, updated it to the latest build, and enrolled it. During enrollment, I immediately noticed a difference. As shown below…. the secure boot policy that Microsoft says isnt’t working on Pro devices… is being applied successfully!

From there on, I opened the registry and executed slmgr /dlv. I guess it’s now pretty obvious. Secure Boot and the policy is rejected by licensing (65000) issue, is caused by subscription activation! Subscription Activation gives the device just a different type of SKU… with it the SLAPI engine rejects that policy for that SKU.

To be sure my eyes weren’t deceiving me, I also executed the licensingdiag command to check the WindowsPolicydata. As shown below, secure boot is indeed in the PolicyMDMAllowList!

So the Known issue that Microsoft is talking about needs some adjustment….

The Full Policy Is Rejected by Licensing Flow, End to End

With the full picture, here is the flow of how the policymanager.dll handles the policy and determines whether it’s allowed. (aka policy is rejected by licensing)

Why Microsoft Can Fix This Without Touching the Device

What makes this issue extra confusing is that Microsoft can already fix it without even touching the device. Every Windows device periodically checks in with the Microsoft licensing service. During that check-in, roughly every 30 days, Windows refreshes its entitlement data and rebuilds the evaluated licensing state locally.

When the 65000 error, rejected by licensing, is caused by an incorrect licensing evaluation, Microsoft can fix it service side by updating the licensing information used during subscription activation. The next background license refresh is then enough for the Secure Boot policy to start applying. No Windows update. No Intune change. That is why some devices appeared to fix themselves weeks later.

The downside is obvious. Waiting up to 30 days for a policy to unblock itself is not exactly a strategy.

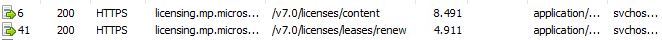

This is where the CLIP cleanup comes in. Running rundll32 clipc.dll,ClipCleanUpState forces Windows to discard its current licensing state and rebuild it immediately (don’t do this in prod). After a reboot, the device connects to licensing.mp.microsoft.com, retrieves fresh license content, and renews its license.

Once that happens, the local licensing evaluation is recalculated, and the Secure Boot capability suddenly reappears on the MDM policy allow list. With the policy showing up in the MDM Policy allowlist… the policy will also be successfully applied to the device!

After the policy is applied to the device, the policy in Intune will also no longer show the error 65000

In other words, the command does not fix licensing. It accelerates what Windows and Microsoft’s licensing service were already going to do anyway. Instead of waiting for the next scheduled entitlement refresh, you trigger it on demand. Luckily, Microsoft also added a possible fix… and when looking at it, it’s a better and safer approach than the clipcleanupstate command I used 😉

- ClipDLS.exe removesubscription

- ClipRenew.exe

Final Thoughts

Windows makes this decision, not Intune. Intune delivers the policy, but SLAPI is the engine that decides whether it is allowed. When that check returns policy is rejected by licensing, nothing is applied and Intune can only report the generic result. If you want to validate the real decision, LicensingDiag is the most reliable way to see the evaluated MDM allow list.

Even after fixing the licensing side, one problem remains: there is still no real Secure Boot rollout status view in Intune. That missing Secure Boot Status report seems to be what Microsoft is building next. Check out this additional blog for all the details!